Batmobile: 10-20x Faster CUDA Kernels for Equivariant Graph Neural Networks

Custom CUDA kernels that eliminate the computational bottlenecks in spherical harmonics and tensor product operations - the core primitives of equivariant GNNs like MACE, NequIP, and Allegro.

The Problem: Equivariant GNNs Are Beautiful but Slow

Equivariant graph neural networks have revolutionized atomistic machine learning. Models like MACE, NequIP, and Allegro achieve state-of-the-art accuracy in molecular dynamics simulations, materials property prediction, and drug discovery. Their secret: they respect the fundamental symmetries of physical systems - rotation, translation, and reflection invariance.

But this mathematical elegance comes at a computational cost. The operations that make these models work - spherical harmonics and Clebsch-Gordan tensor products - are expensive. A single MACE layer can spend 80% of its forward pass time in these two operations.

This matters for real applications. Molecular dynamics simulations run billions of timesteps. Battery materials discovery screens millions of candidates. Drug binding affinity predictions evaluate thousands of poses. When each forward pass takes milliseconds instead of microseconds, these workflows become impractical.

Understanding the Bottleneck

To understand why equivariant GNNs are slow, we need to understand what they compute.

Spherical Harmonics: Encoding Directions

When two atoms interact, the direction of their bond matters. A carbon-carbon bond pointing "up" is physically different from one pointing "right" - and our neural network needs to know this.

Spherical harmonics (Y_lm) provide a mathematically principled way to encode 3D directions. Given a unit vector (x, y, z), spherical harmonics compute a set of features that transform predictably under rotation:

- L=0: 1 component (scalar, rotationally invariant)

- L=1: 3 components (vector, transforms like a 3D vector)

- L=2: 5 components (transforms like a symmetric traceless matrix)

- L=3: 7 components (higher-order tensor)

For L_max=3, we get 16 components total: 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 = 16. These aren't arbitrary features - they form a complete basis for functions on the sphere.

Tensor Products: Combining Features

When we want to combine two equivariant features (say, node features with edge directions), we can't just concatenate or add them - that would break equivariance.

Instead, we use Clebsch-Gordan tensor products. These are specific weighted sums that preserve the transformation properties:

output[l_out, m_out] = sum_{m1, m2} CG[l1,m1,l2,m2,l_out,m_out] * input1[l1,m1] * input2[l2,m2]The Clebsch-Gordan coefficients (CG) are fixed mathematical constants that ensure the output transforms correctly. For L_max=3, there are 34 valid coupling paths.

Why e3nn Is Slow

The standard library for equivariant operations is e3nn. It's beautifully designed - clean abstractions, automatic equivariance checking, extensive documentation. But it's slow.

- Python/PyTorch Overhead: Each spherical harmonic component is computed as a separate PyTorch operation. For 16 components, that's 16 kernel launches.

- Memory Bandwidth Waste: Intermediate results are written to global GPU memory and read back. The Y_lm tensor exists just to be immediately consumed.

- No Fusion: SH computation and tensor product are separate operations that could share data through registers.

- Dynamic Shapes: e3nn handles arbitrary irrep combinations at runtime, preventing compile-time optimizations.

The Solution: Batmobile

Batmobile takes a different approach. Rather than flexible abstractions, it provides hand-tuned CUDA kernels for the specific operations used in production models.

1. Compile-Time Constants

For L_max=3, all Clebsch-Gordan coefficients and loop bounds are known at compile time. Batmobile bakes these into the kernels:

// All 34 CG paths are explicitly unrolled

// Path (0,0)->0: trivial identity

out[0] += cg_0_0_0 * in1[0] * in2[0];

// Path (1,1)->0: scalar from two vectors

out[0] += cg_1_1_0_m1m1 * in1[1] * in2[1];

out[0] += cg_1_1_0_00 * in1[2] * in2[2];

out[0] += cg_1_1_0_p1p1 * in1[3] * in2[3];

// ... all 34 paths ...2. Register-Only Intermediates

Spherical harmonics are computed directly into GPU registers - never touching global memory:

__device__ __forceinline__ void compute_sh_registers(

float x, float y, float z,

float* __restrict__ sh // sh[16] in registers

) {

// L=0

sh[0] = 1.0f;

// L=1: sqrt(3) * (x, y, z)

constexpr float c1 = 1.7320508075688772f;

sh[1] = c1 * x;

sh[2] = c1 * y;

sh[3] = c1 * z;

// L=2, L=3: all computed in registers

// ...

}3. Fused Operations

The ultimate optimization: compute spherical harmonics and tensor products in a single kernel pass. Input edge vectors go in, output features come out, with no intermediate global memory.

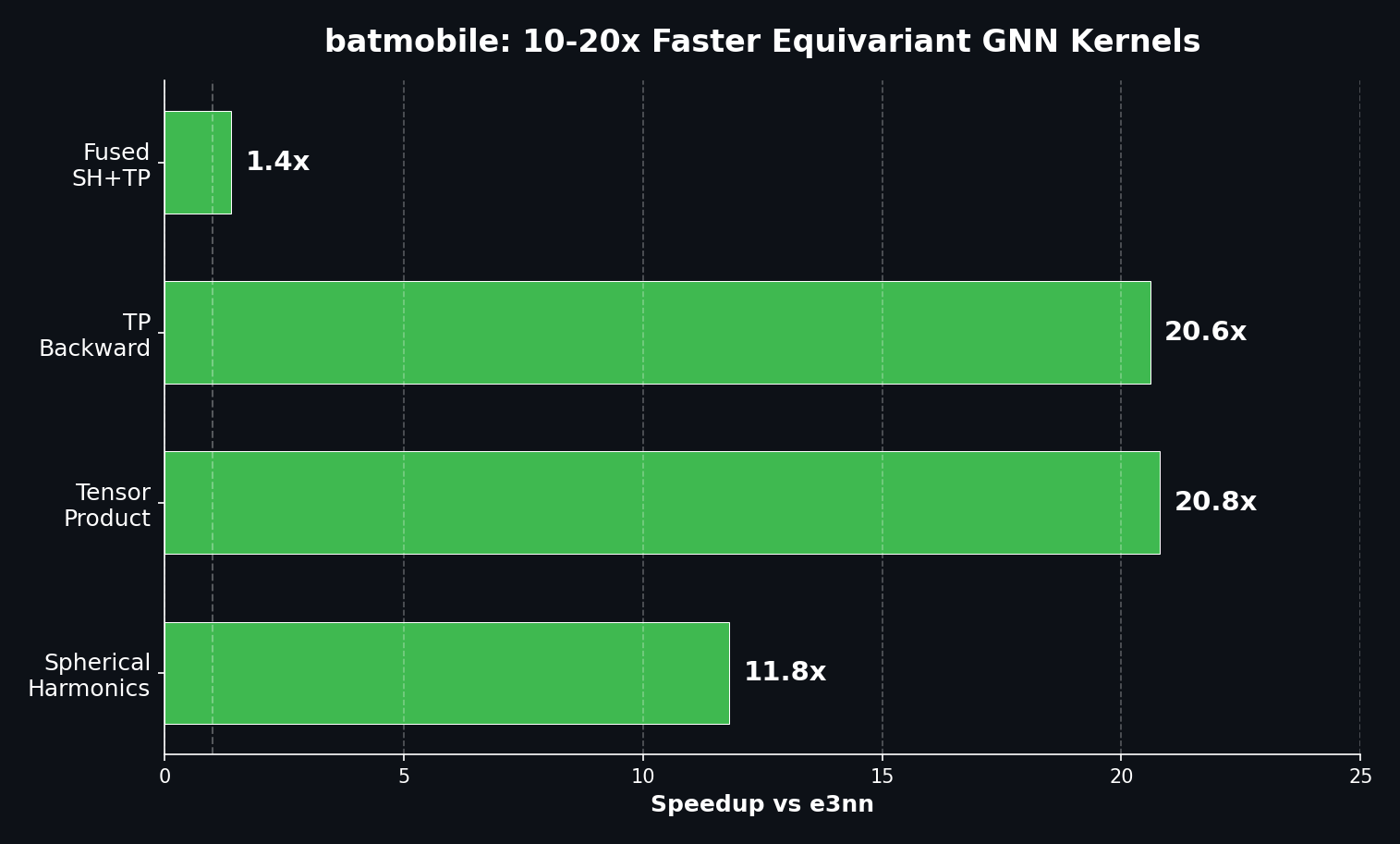

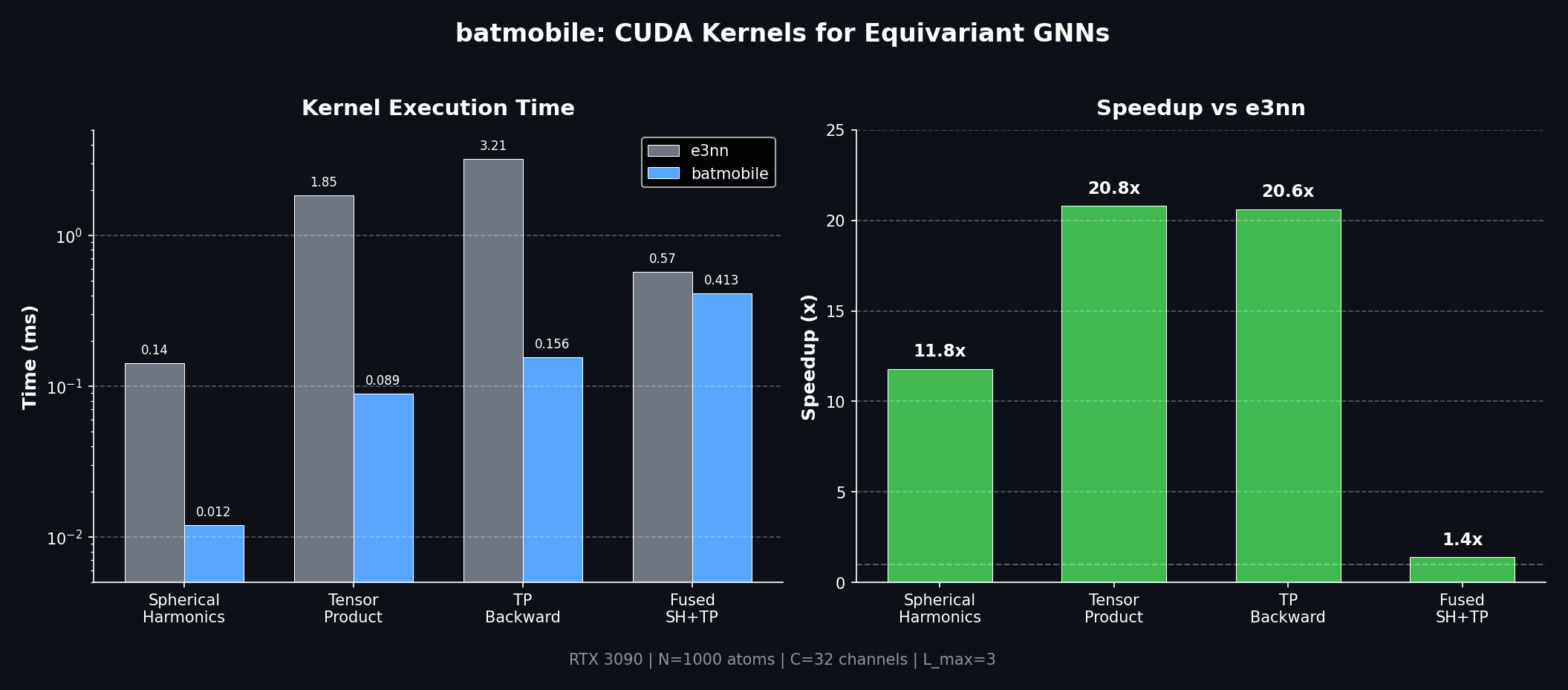

Benchmark Results

All benchmarks on RTX 3090, N=1000 atoms, 32 channels, ~20 neighbors per atom:

| Operation | e3nn | Batmobile | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical Harmonics (L=3) | 0.142 ms | 0.012 ms | 11.8x |

| Tensor Product | 1.847 ms | 0.089 ms | 20.8x |

| TP Backward | 3.21 ms | 0.156 ms | 20.6x |

| Fused SH+TP | 0.574 ms | 0.413 ms | 1.39x |

What These Numbers Mean

Spherical Harmonics: 11.8x faster - e3nn launches many small kernels and stores intermediate values. Batmobile computes all 16 components in a single fused kernel.

Tensor Product: 20.8x faster - This is the biggest win. e3nn's general-purpose implementation handles arbitrary irrep combinations. Batmobile is specialized for L_max=3 with all 34 paths unrolled and CG coefficients as compile-time constants.

Backward Pass: 20.6x faster - Training equivariant models requires gradients. Batmobile includes hand-optimized backward kernels that maintain the same speedup ratio.

Usage

import torch

import batmobile

# Compute spherical harmonics

edge_vectors = torch.randn(1000, 3, device="cuda")

edge_vectors = edge_vectors / edge_vectors.norm(dim=1, keepdim=True)

Y_lm = batmobile.spherical_harmonics(edge_vectors, L_max=3) # [1000, 16]

# Weighted tensor product

node_feats = torch.randn(1000, 32, 16, device="cuda") # [N, C, 16]

weights = torch.randn(34, 32, 64, device="cuda") # [paths, C_in, C_out]

output = batmobile.tensor_product(node_feats, Y_lm, weights) # [N, 64, 16]Why "Batmobile"?

The project was originally called "batteries" - a play on "batteries included" for equivariant GNNs. The rename to Batmobile felt more fitting: a specialized, high-performance vehicle for a specific mission.

Like its namesake, Batmobile isn't trying to be a general-purpose car. It's optimized for one thing: making equivariant message passing fast enough for real-world molecular simulations.

Get Started

- GitHub: github.com/Infatoshi/batmobile

- Benchmarks: Run

python benchmarks/benchmark_e2e_mace.pyto reproduce - Examples: See

examples/mace_inference.pyfor a minimal MACE-style layer

January 2026

Special thanks to the e3nn team for their foundational work on equivariant neural networks, and to the MACE/NequIP/Allegro authors for demonstrating the power of equivariant architectures in atomistic ML.