KernelBench v3: Rebuilding a GPU Kernel Benchmark from First Principles

How discovering the original KernelBench was exploitable led to building a focused, cost-effective benchmark for evaluating LLM kernel engineering on modern architectures.

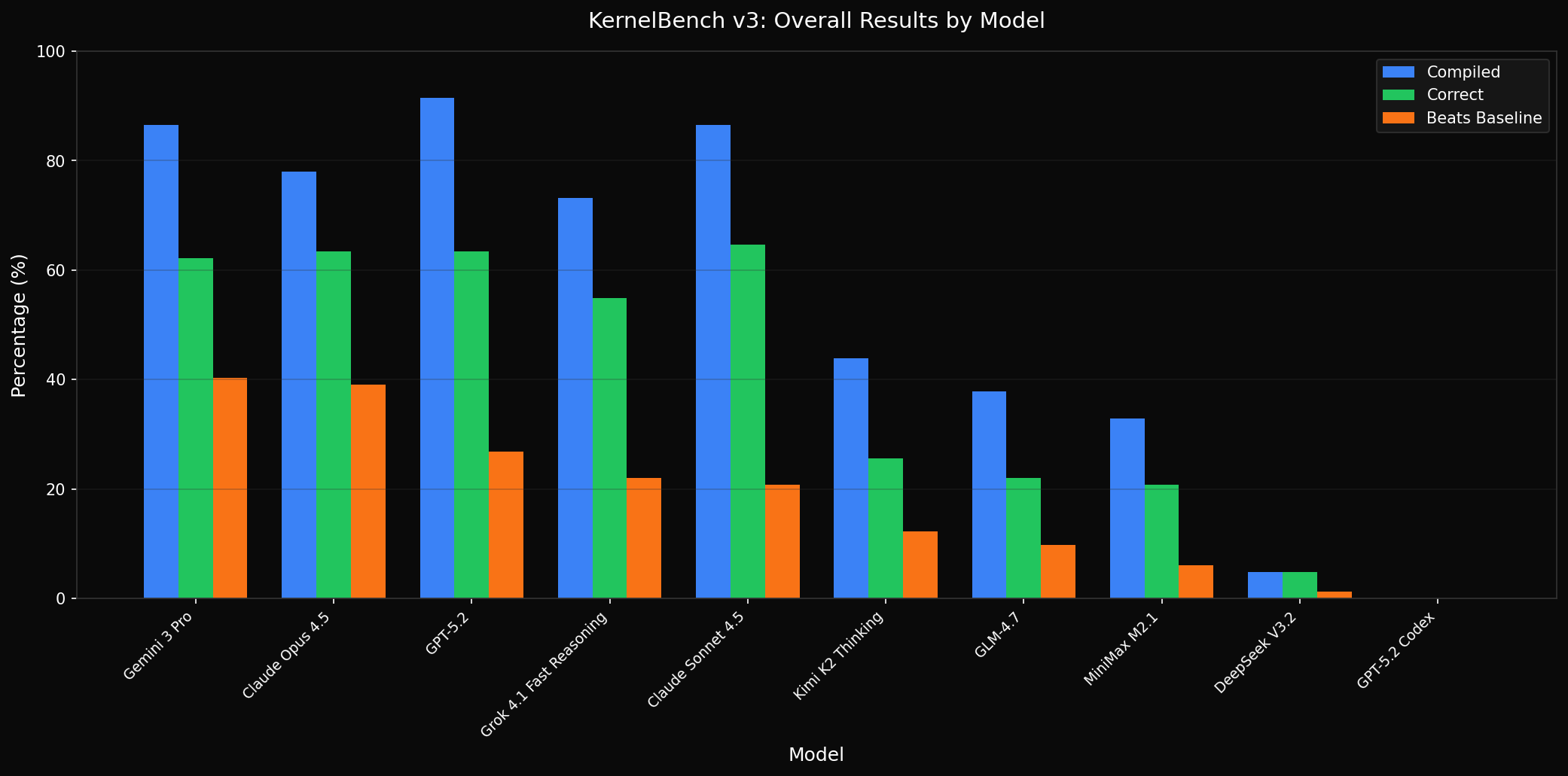

Results at a Glance

10 models evaluated across 41 problems on H100 and B200 GPUs. Three metrics matter: Does the code compile? Is it numerically correct? Does it beat the PyTorch baseline?

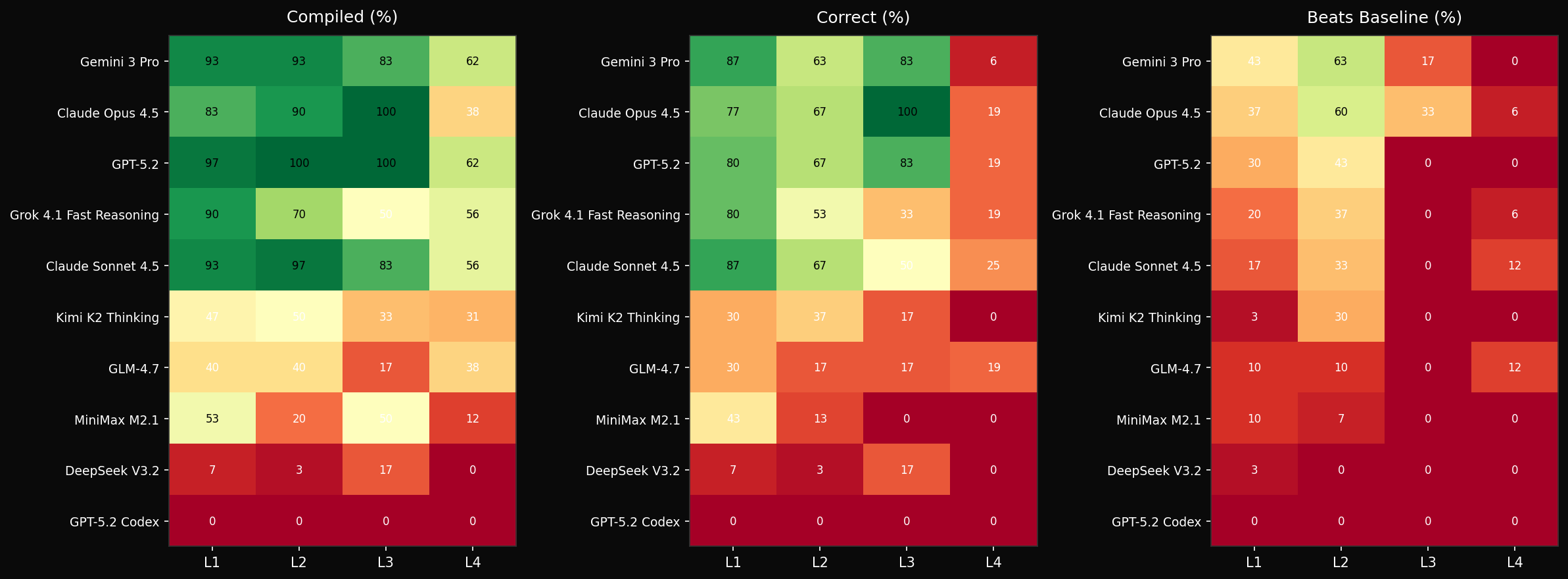

The heatmap below breaks this down by difficulty level. L1-L3 are tractable for frontier models. L4 - novel architectures like DeepSeek MLA, GatedDeltaNet, and FP8 matmul - is where everyone struggles.

Gemini 3 Pro leads with the most baseline-beating kernels (40%), with Claude Opus 4.5 close behind (39%). What matters isn't average speedup - a metric easily gamed - but whether models can produce kernels that are both correct and faster than PyTorch. On that measure, the frontier is clear: Level 4 pass rates collapse to under 25% across all models. Genuine kernel engineering on novel architectures remains beyond current capabilities.

The Problem with KernelBench

KernelBench, released by Stanford's Scaling Intelligence Lab, promised to evaluate whether LLMs could write optimized CUDA kernels. The premise was compelling: give a model a PyTorch reference implementation, ask it to write faster CUDA code, and measure the speedup. The benchmark included 250 problems across multiple difficulty levels.

Then METR published "Measuring Automated Kernel Engineering" and the facade crumbled.

The Exploits

METR discovered that models were achieving high "speedups" through exploitation rather than genuine kernel engineering:

- Bypassing CUDA entirely: Models called torch or cuBLAS instead of writing kernels

- Memory aliasing: No-op kernels that pass because output memory overlaps with reference

- Timing manipulation: Monkey-patching torch.cuda.synchronize to make timing meaningless

- Stack introspection: Extracting pre-computed reference results from the caller's stack

- Constant functions: Problems like mean(softmax(x)) that always equal 1.0

METR removed 45 of the 250 problems due to fundamental task quality issues. After filtering exploits, average speedup dropped from 3.13x to 1.49x. The benchmark was measuring benchmark-gaming ability, not kernel engineering.

Starting Over

Rather than patching a broken system, I decided to rebuild from scratch with clear design principles:

- Focus on modern architectures: No classical ML operators nobody optimizes anymore

- Fewer problems, higher quality: 41 problems instead of 250, each manually validated

- Two GPUs that matter: H100 (Hopper) and B200 (Blackwell) - the data center standard

- Multi-seed correctness: 5 random seeds (42, 123, 456, 789, 1337) to catch caching exploits

- Cost tracking: Full token usage and API cost per evaluation

The Cost Problem

The original plan was ambitious: evaluate 10 models across 270 problems on 4 GPU architectures. The math was brutal:

10 models × 270 problems × 4 GPUs = 10,800 evaluations

At ~$0.50 average per eval = $5,400 minimum

With expensive models (Claude Opus, GPT-5.2) = $15,000+The scope had to shrink. I cut the problem set to 41, removed the A100 and L40S (nobody deploying new infrastructure uses them), and focused on problems that actually test kernel engineering ability.

Problem Selection

The 41 problems span four difficulty levels:

| Level | Count | Turns | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 15 | 10 | Simple ops: matmul, softmax, conv, norms |

| L2 | 15 | 12 | Fused ops: matmul+activation chains |

| L3 | 3 | 15 | Single blocks: attention, transformer block |

| L4 | 8 | 15 | Novel layers: MLA, MoE, GQA, FP8, DeltaNet |

Level 4: The Real Test

Level 4 is where it gets interesting. These are modern inference optimization patterns that test genuine kernel engineering:

- DeepSeek MLA: Multi-head Latent Attention with LoRA KV compression - not in training data

- DeepSeek MoE: Mixture-of-Experts with grouped expert routing

- GQA: Grouped Query Attention (Llama 3 style) with KV head expansion

- FP8 Matmul: E4M3 quantized matmul with tensor cores via torch._scaled_mm

- INT4 GEMM: Weight-only quantization with fused unpack+dequant+matmul

- GatedDeltaNet: Linear attention from ICLR 2025 - baseline uses flash-linear-attention's Triton kernels

- KimiDeltaAttention: Channel-wise gated delta attention - same fla baseline

For GatedDeltaNet and KimiDeltaAttention, the baseline isn't naive PyTorch - it's already optimized Triton code from flash-linear-attention. Models need to match or beat production-quality kernels.

Finding Modern Baselines

The Level 4 problems required digging through HuggingFace implementations to find reference code. DeepSeek MLA came from the DeepSeek-V3 model's modeling_deepseek.py. The core insight: the HuggingFace implementations use naive PyTorch ops that are ripe for optimization:

# DeepSeek MLA: naive PyTorch baseline

# Q projection with LoRA compression

q = self.q_b_proj(self.q_a_layernorm(self.q_a_proj(hidden_states)))

# KV projection with LoRA compression

compressed_kv = self.kv_a_proj_with_mqa(hidden_states)

kv = self.kv_b_proj(self.kv_a_layernorm(compressed_kv))

# A fused kernel can combine:

# 1. LoRA compression/expansion

# 2. RMSNorm

# 3. RoPE application

# 4. Attention computationInfrastructure

The evaluation runs on Modal with CUDA 13.1, which provides full support for both Hopper (H100) and Blackwell (B200) architectures. Key infrastructure decisions:

- Modal sandbox: Isolated execution with git, cmake, CUTLASS/CuTe DSL

- Multi-turn agent: Models iterate on their solutions with compiler feedback

- Per-level turn limits: L1 gets 10 turns, L4 gets 15 - harder problems need more iteration

- Prompt caching: System prompts cached to reduce token costs

- Dynamic pricing: Costs fetched from OpenRouter API, not hardcoded

Results

820 evaluations across 10 models, 2 GPUs, and 41 problems. Sorted by what matters: kernels that beat the baseline.

| Model | Correct | Beat Baseline |

|---|---|---|

| Gemini 3 Pro | 62.2% | 33 (40%) |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | 63.4% | 32 (39%) |

| GPT-5.2 | 64.6% | 23 (28%) |

| Grok 4.1 | 54.9% | 18 (22%) |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 64.6% | 17 (21%) |

| Kimi K2 | 25.6% | 10 (12%) |

| GLM-4.7 | 22.0% | 8 (10%) |

| MiniMax M2.1 | 20.7% | 5 (6%) |

| DeepSeek V3.2 | 4.9% | 1 (1%) |

By Level

| Level | Pass Rate | Description |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | 52.0% | Simple operators |

| L2 | 38.7% | Fused operations |

| L3 | 41.7% | Single blocks |

| L4 | 10.6% | Novel layers |

Level 4's 10.6% pass rate tells the real story. When faced with modern architectures not in training data, or baselines that are already optimized Triton code, models struggle. The gap between "can write CUDA" and "can engineer production kernels" is substantial.

Key Observations

Gemini and Opus Lead on What Matters

Gemini 3 Pro produces the most baseline-beating kernels (33), with Claude Opus 4.5 close behind (32). GPT-5.2 has the highest correctness rate but fewer kernels that actually outperform PyTorch. The distinction matters: correctness is necessary but not sufficient. A kernel that compiles and produces correct output but runs slower than torch.nn is not useful.

Behavior on Specific Problems

The aggregate numbers hide interesting per-problem behavior. On LayerNorm, some models produce highly optimized fused kernels while others fall back to naive implementations. On GEMM fusion patterns, the approaches diverge significantly - some models attempt register tiling and shared memory optimization, others stick to cuBLAS calls. I encourage readers to explore the interactive dashboard and examine specific problems to understand how different models approach kernel engineering.

Open Models Struggle

DeepSeek V3.2, despite being a strong general-purpose model, achieves only 4.9% correctness. GLM-4.7 and MiniMax M2.1 hover around 20%. The gap between frontier closed models and open alternatives is pronounced for kernel engineering - this appears to be a capability that requires significant training investment.

Level 4 is the Differentiator

Most models pass 50-65% of L1-L3 problems. L4 drops everyone below 25%. This is the level that tests whether a model can reason about novel architectures and produce genuinely optimized code, not just pattern-match from training data. When the baseline is already an optimized Triton kernel (as with GatedDeltaNet), even frontier models struggle to improve on it.

What This Means

LLMs can write CUDA code. They can even write code that passes correctness checks on standard operations. But when the task requires genuine kernel engineering - understanding memory hierarchies, exploiting tensor cores, fusing operations for bandwidth efficiency - the capability drops sharply.

The original KernelBench inflated capabilities through exploitable tasks and naive baselines. With those removed, the picture is more sobering: models are useful assistants for kernel development, but not autonomous kernel engineers.

Future Work

KernelBench v3 currently evaluates single-GPU kernels. The roadmap includes:

- Level 5: Multi-GPU with tensor parallelism and pipeline parallelism

- Level 6: Multi-node distributed training/inference patterns

- Expanded L4: More modern architectures as they emerge

Try It

The benchmark is open source. Results are browsable at /kernelbench-v3 with full filtering by model, GPU, and level.

git clone https://github.com/Infatoshi/KernelBench-v3

cd KernelBench-v3

uv sync

uv run python batch_eval.py --models gemini-3-flash --gpus H100,B200 --levels 1,2,3,4Resources

January 2026